Tracking Advanced Port Scanning

This is from a recent week of scans. 330 seems like a lot for this new technique, even for a site that is regularly targeted, but then again I don’t have a lot of data to compare to.

Is it possible to detect and even react to port scanning that is happening against an online asset you’re charged with protecting? Absolutely. But there is a somewhat advanced scan technique I’ve noticed against the public-facing NMRC servers, and while other defenses are in place to protect things, I started taking steps to actually try and detect it myself. This is not just about how I approached it, but I even started writing some code to make it easier to detect.

Apparently distributed scanning techniques are becoming more common, last month I detailed how I was seeing a distributed scan against the NMRC mail server and defenses I set up. It makes sense that I either set up defenses for this new thing, or at least monitor for similar techniques applied by scanners looking for open ports to attack.

The Old SCANNING Method

This is a quick recap for those reading who have little to no idea what port scanning is. The regular old port scan can be somewhat easy to detect. Logs on the target system will show connection attempts that are blocked by a local firewall, and between the responses to each TCP (and UDP as well, assuming that is being probed) there might be some connections on open ports. The most common ones are ports used by web traffic such as 80 and 443, although a few extra do turn up on less common ports. There’s also mail (port 25), SSH (port 22), and many others. The point of a port scan is to try and identify services being offered by an IP address, and if your intent as the person doing the port scan is malicious, you can end up with a handful of services on the target you could try to exploit - typically to gain unauthorized access.

Entire tools, security conference presentations, defense strategies, and features in defensive products surround this phenomena, people have written chapters in security books on the topic, and even entire books exist on this exact subject. As a result, there are defenses in place that one can set up to thwart the malicious port scanner. These usually involve looking for the patterns of repeated connections from a source IP looking at various ports and trying to make enough of a connection to validate an open port has been found, and even optionally try to verify the service running on that port. By studying these patterns there are tools and strategies that exist that can create stronger defenses via automation, allowing an administrator to rest easier knowing that at least one data-gathering technique that is often used as recon prior to an attack has been thwarted.

A New Scanning Method

This is different. Knowing what the various automations are that can detect and thwart scans would allow a malicious actor to still get the desired result - a successful port scan. It seems most automated systems look for specific types of patterns which include the following:

A series of connection attempts, either blocked or allowed, from a single IP address.

Each connection attempt is to a different destination port.

All the connects occur within a fairly short timeframe, often within seconds of each connection.

Most automated systems can easily spot these patterns and automatically block the IP address in question. So what some actors are doing to get around being spotted is the following:

There is a series of connection attempts, either blocked or allowed, coming from multiple IP addresses.

Each connection attempt, like a normal port scan, is to a different destination port.

A connection from a single IP address is attempted, and subsequent connections from that same IP address will be spaced out by minutes or hours, sometimes only occurring once per day, but often in a time frame that is slightly over one hour.

The multiple IP addresses are often found coming from the same class C of IP addresses, with most of them being non-sequential. For example, a group of five IP addresses doing this, they are typically not all in the same /29 but they are on the same /24.

I am not 100% sure if they are spread out over a class B, or there are groups of class Cs on completely different ISPs working together, mainly because it would require a more sophisticated level of detection (most likely based upon destination port being unique between two or more class C clusters).

Detection

It is possible to detect this type of activity, as it can be fairly easy to spot the pattern of a single cluster from a class C. Once you know what you are looking for, it isn’t too hard to at least automate detection. And even though I spotted this over two years ago, I finally got around to actually ditching my grep-heavy bash scripts and coded up something a bit more “shareable” in Python. What it does is have some thresholds that must be met before it will “trigger” and start collecting the data from logs. For me, it seemed easier to hone in on my rsyslog server as I could check more than one system at a time for a scan (I have a /29, multiple IPs that get scanned). The firewall for each server is a fairly simple UFW setup for the four public servers that talk to the Internet, so the regex is the Python looks for that. And there are plenty of scan attempts, as NMRC has a history of being regularly attacked. Plus, as they are public IP addresses on the open Internet, it is not uncommon for those with the patience and time to just scan away at anything and everything.

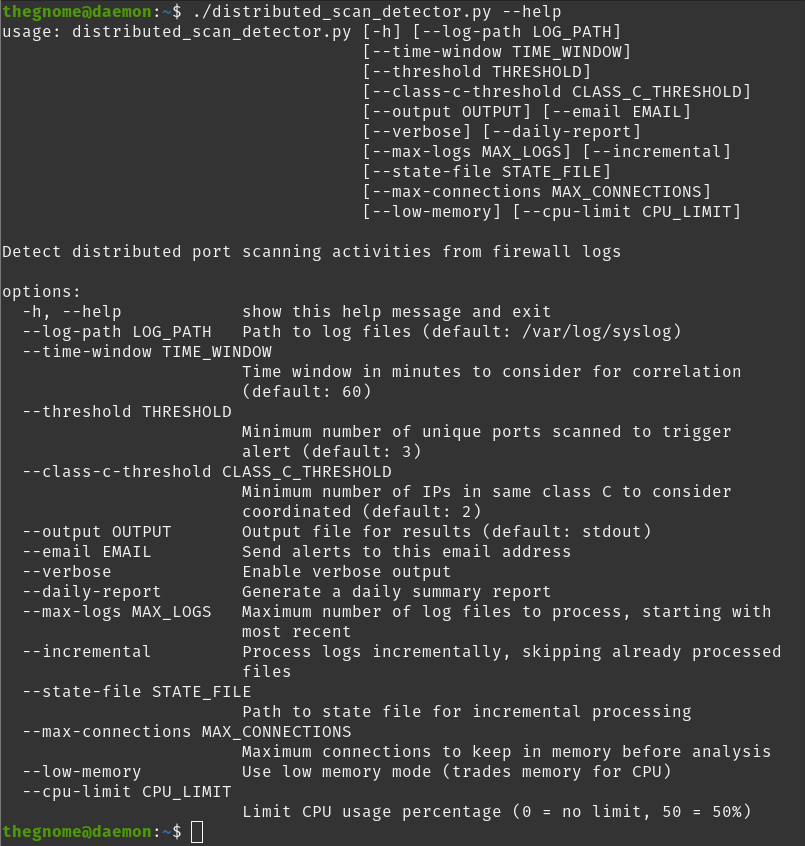

Output from the app’s help function.

Initial testing was fine, although I wasn’t grouping the scanning IP addresses correctly, so I fixed that. Additionally it really killed the CPU and drove the temperature up quite a ways, so I’ve made numerous adjustments to improve performance, and added some parameters that one can tweak to further help as needed. I’ve also written a bash script to be called from crontab to help automate the running of the tool, although one could run the python app locally on downloaded syslog files. It can handle gzip files, even multiple files, and incrementally go through them. Maybe in the future I’ll add database support for more longer term data analysis, but for now it does what I need it to do.

If you’re interested in this at all, check out the repository for the code here: https://gitlab.com/nmrc/advanced-network-scanning. Yes it is also on the NMRC GitLab instance, however if people want to contribute they can do so on the GitLab server (the NMRC server is for NMRC members only).

Did I use AI to write the code? Yes and no. I had a general framework and maybe half the code written, asked Claude for some assistance, then in a separate chat asked for a check for security flaws. I had the results from CI testing in GitLab so I knew what was potentially flawed, and Claude found the same flaws and offered up fixes. I actually really like Claude’s style of indentation and frequent commenting (I’m trying to get better at comments myself) so I’ve tried adopting that into my own coding attempts. A lot of the performance improvements were suggested by Claude, so I leaned into that advice as well. I didn’t use everything because a lot of it was simply unneeded, but good stuff overall.

Who Is Behind This?

Good question. No idea who is doing this type of scanning. I will say there are firms that do slow scans like this for general intel that they put up publicly, and there are certainly malicious actors out there doing it as well. But for me, step one was gathering of the raw data about the scans themselves, and maybe further down the line this will lead to other data that actually garners some answers. Right now the answers I’m getting raise more questions. For example, in the screen grab picture for this blog post up above, the scanning class C 100.29.192.0/24 over the course of a week checked for only 7 ports, with the majority of them dealing with management of either specific technical products or systems. It was like the actor had a group of random exploits to try and started looking for opportunity, but who knows? Maybe the actor’s botnet had nodes on other class Cs that when you combined the efforts it told a more clear story.

Regardless, fascinating data to play with and think about. I hope you’ve found this information at least interesting, maybe even useful!

[Edit: It has been pointed out that this could also be an automated tool that is attempting attacks such as brute force type attacks (hence the sheer number of connections) but there is also ample evidence from other data that suggests one connection per port, implying a port scan. This seems to be the main thing I am seeing.]