Ultimate Encryption Solution

Photo by Oyemike Princewill on Unsplash

Is there an absolutely 100% secure encryption algorithm? Yes! Did I write one? Yes! Do I use it all the time? Well…..

There are good encryption algorithms and bad encryption algorithms. I found a really good one a long time ago, and wrote up a proof-of-concept command line program for it. Written in C, I knew then and I know now that it isn’t exactly useful. So naturally I decided to rewrite it. Why? We’ll get into that.

What is this ultimate algorithm?

It is the One Time Pad (OTP). Basically you take a random number generator and generate a large chunk of data we’ll call a “pad”. Alice takes a copy of this pad and gives it to Bob. When Alice wants to send Bob a secret message, she encrypted the message with the pad and then sends the message to Bob. When Bob receives the message, he decrypts it with the pad. Afterwards Alice and Bob both destroy the pad, hence the reference to it being used only once, aka “one time pad”. The encryption algorithm? XOR. So this is lighting fast to both encrypt as well as decrypt. Simple enough, right?

The clever among you have spotted the immediate problems with this scenario, which are many:

Random source. Basically a computer can do psuedo random number generation (PRNG), a true random source for number generation is hard to come by. This is true, and applies to a lot of cryptographic areas including OTPs. A decent PRNG will most likely suffice in many cases, but there is that ever-so-slight danger. The danger is of course much greater if your adversary trying to crack your encryption is a nation state, specifically the more advanced ones (Five Eyes, Russia, China).

XOR. Sounds weak, doesn’t it? The main thing to keep in mind is some of the properties of using XOR. For example, ASCII plaintext when XORed with any value one ends up with the upper bit as zero statistically more than not. Therefore if the encrypted message is in ASCII, you’ve reduced the character set involved. The best way around this is to compress the message before the XOR operation. This also has the advantage of reducing the size of pad you need.

Pad security. This one is really hard to deal with. Your pad is your encryption/decryption key. For Alice to use OTP to send Bob a message, she has to create a pad and then (this is the hard part) securely get one and just one copy of the pad to Bob before she sends the message. Obviously Alice would not want to simply send Bob an email with the pad as an attachment or something similar. Courier? Can the courier be trusted? If the courier is carrying a pad, couldn’t he just carry the message as well? It gets complicated real fast. In theory you could send one batch of pads via courier with the idea being the courier is sent periodically with more pads, or the courier brings one big pad which is used to encrypt a bunch of compressed pads in a file that are sent via the Internet. Not ideal. Maybe as a part of Alice and Bob’s job they periodically see each other in person and do a pad exchange.

These are some of the technical difficulties with OTPs. Worse is when you involve humans, and introduce a PEBKAC situation. These simply make OTP seem even more impractical.

Pad reuse. The pads are supposed to be used just once. If due to laziness the pads are used more than once, since things evolve around XOR this kind of reduces the effectiveness. In normal human terms, this weakens the algorithm if a pad is reused.

Known plaintext. This is another common cryptographic problem that comes up. If you have known plaintext, such as starting off all encrypted communications with the date in plaintext along with a specific heading and initial greeting, this can weaken things. If this is combined with one of the other problems, this can unravel the encryption entirely. Maybe the known plaintext isn’t a problem, but if the information isn’t compressed before it gets the OTP treatment you’ve reduced the math needs, and then if you reuse a pad it is even worse.

True random source material. If the source of the random material is not truly random, this can mean the pad itself might have some “patterns” in it. Granted the math involved to solve for these patterns is best handled by attackers at a nation-state level, i.e. the NSA.

Some of these weaknesses are explained via this reference. And while you’re at it, for more inspiration regarding that whole PEBKAC angle, check out the Enigma machines and the cryptanalysis work done on them. Yes this is a different algorithm, but it provides more insight into the whole cryptanalysis process, and if you’re a security nerd it will be entertaining reading.

Why rewrite it? And why in C?

I originally wrote it as probably more of an intellectual exercise than a serious attempt at a security tool. Oh, I did try to at least make it functional, and at the time I wrote it (in 2005) I was halfway proficient in C, so it was more of a fun exercise than a serious major code release.

I decided to update this after I kind of stumbled across the code and once again thought this would be a fun exercise. I had a couple of things in mind with this - make it slightly more functional, reduce the needless complexity in the code, update to a better PRNG that could optionally work in a FIPS environment, and push myself in the whole CI/CD process (mainly the CI part).

There is also an underlying property in C, in that it is much lower level than something like Python. Remember, very large chunks of the Internet and underlying operating systems are written in C, so often when I delve into new areas (or areas I want to understand better) I will write whatever it is in C. Granted sometimes it is more of a “first draft” of sorts, but it is highly educational and entertaining. Using a new PRNG solution brought this up in my mind, and just getting the code to cleanly build in several different Linux distributions was challenging. It was especially challenging because when I say “clean build” I don’t just mean “no errors”. I mean “no warnings” either. As some of the SAST tools are a bit lacking for C, getting extra things working besides cppcheck (like valgrind and flawfinder) were an interesting exercise.

Did I use AI? Yes, but mainly to check my work. I’d ask for a scan for security flaws in my code. I’d validate my approach to what I was doing in my .gitlab-ci.yml file. I’d make sure my Makefile wasn’t insane (or too sane, if you know what I mean). It helped things evolve.

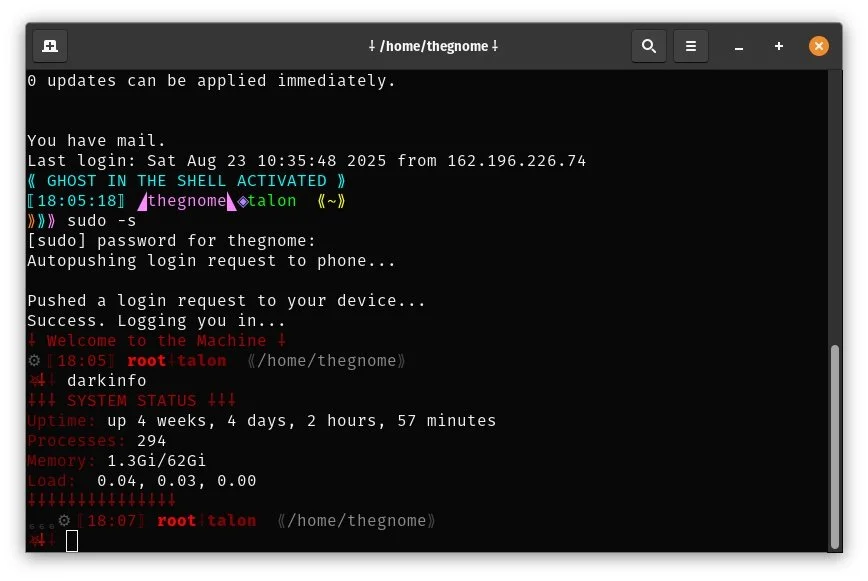

the Code

The code itself assumes Linux, and uses OpenSSL, and the underlying source of randomness is a Deterministic Random Bit Generator (DRBG). DRBG gathers entropy from /dev/urandom. Essentially when calling for random bytes (via the RAND_bytes function), DRBG generates the requested number of bytes, drawing from its internal state which is kept unpredictable by entropy gathered from the operating system.

As there is a NIST-certified version of OpenSSL that meets FIPS 140-3 standards, the code will work if the host operating system is running in FIPS mode. The code does not need to do anything at all and no special flags are required.

The project itself is called Nearly Perfect Crypto and can be found here: https://gitlab.com/nmrc/npc/. It is called Nearly Perfect Crypto because it is not perfect, especially since the random source is not truly random, but pseudo random.

Conclusion

Yes, mainly a coding exercise but an educational one. Feel free to explore and even contribute, this has been a fun project for me to play with and learn from, which is the point of most of this anyway. And hopefully the fact that we’re talking about encryption and personal security in general it gets people to start thinking more about topics like personal security and privacy.

[Edits: A number of people disagreed with me on the part where I mention XORing ASCII text is less secure, so I did reword things. I don’t dismiss the concept as my information was “validated” by a cryptographer who used to work at the NSA, and I believe them as they’ve been right on numerous other things. Using 7bit ASCII reduces the number of characters to analyze against, and with upper bits all zeroes there are patterns that form, hence more insecure. I’ve also updated the code to remove the AES-CTR bit as well as generating a separate “key” for generating pads. The AES-CTR part was overkill as RAND_bytes() is more than enough, and a separate key really not needed and possibly a slight security risk. -ML 2025Jul21]